William Wigglesworth prided himself on three things: his deeply furrowed brow, his capacity for mistrust, and the fact he had once successfully returned a broken toaster to Argos without a receipt.

Which is why, on the morning of April the First, when his wife Wendy announced—over a slice of underdone toast—that they had won the lottery, he responded with the measured dignity of a man who had once been tricked into believing the dog could talk.

“Oh no,” he said, squinting suspiciously over his reading glasses. “Not this again.”

Wendy, who had long since stopped expecting enthusiasm from her husband and had instead settled for signs of basic mammalian function, placed the winning ticket gently on the kitchen table like it was a particularly smug insect.

“There. See for yourself.”

William leaned forward, sniffed the ticket, tapped it twice (for luck or logic, it was never clear), then pushed it away as though it were radioactive.

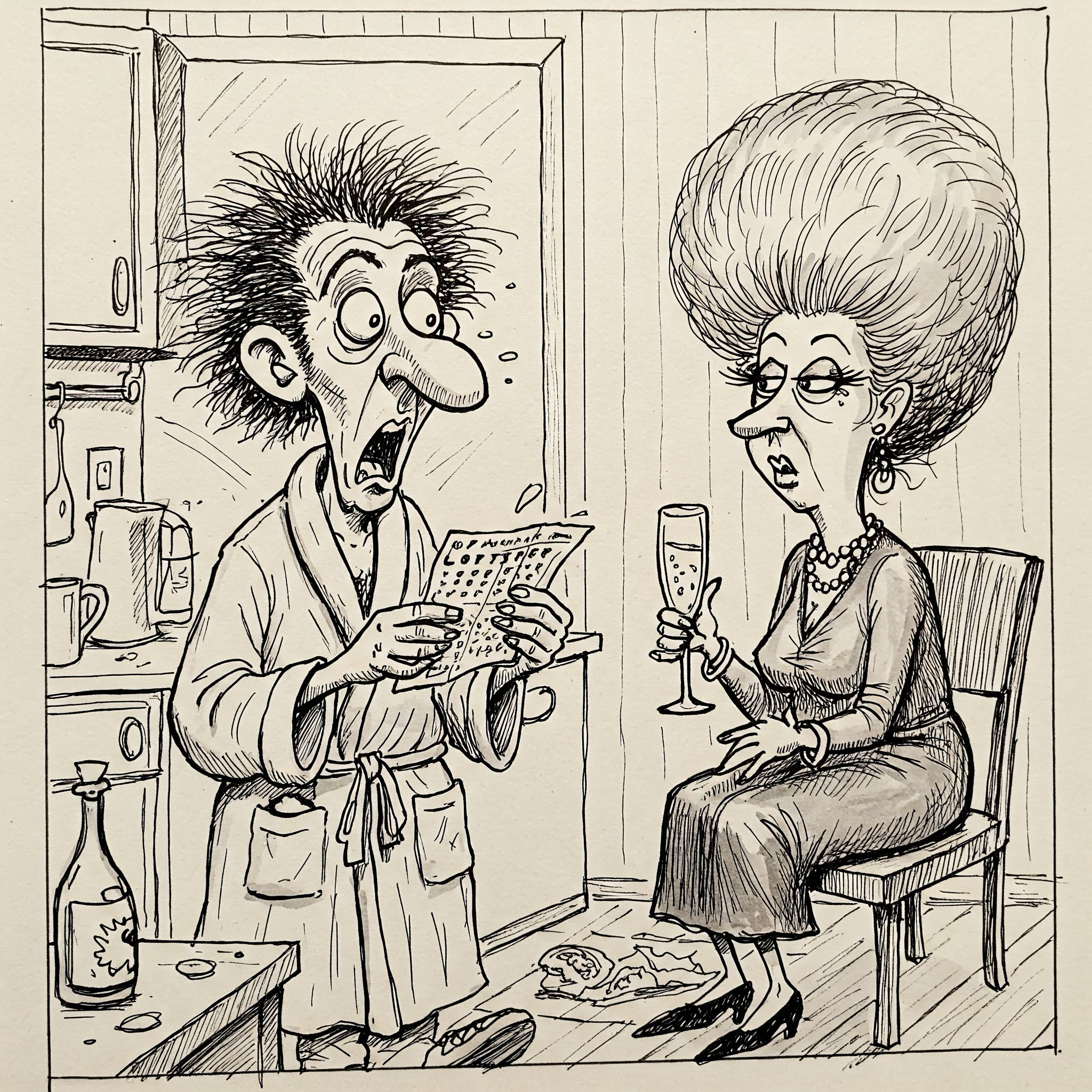

“Do you honestly think,” he began, adjusting his dressing gown like a barrister preparing for closing arguments, “that I, William Barnabus Wigglesworth, would fall for an April Fool’s prank so… pedestrian?”

“It’s not a prank, William,” she said, buttering her toast with alarming force. “It’s a win. Six numbers. And the bonus ball. I triple-checked it.”

William snorted. “Triple-checking is exactly what you’d say if it were a prank. That’s what makes it clever. Too clever.”

Wendy gave him a look that could curdle milk.

“For heaven’s sake, ring the number on the back of the ticket,” she said. “Or go online. Or do whatever it is you do when you need to feel superior to everyone in a three-mile radius.”

He snatched the ticket up, turned it over, and pulled out his phone. Then paused.

“Wait. No. This is how they get you. I go online, I input all my personal details, and next thing I know I’ve signed up for goat yoga and some poor woman in Uganda is being charged £9.99 a minute to listen to me breathe.”

Wendy took a deep breath. Not for relaxation purposes—more to stop herself from hurling the marmalade jar through the nearest window.

“Fine,” she said. “I’ll take it down to the shop. I’ll get it scanned. And when I come back with confirmation that we’re millionaires, you can explain to the Daily Mail why you’re still in your pants.”

“You’re going outside in those slippers?” William asked, scandalised.

She left without answering. She had long since stopped explaining things to William. The last time she’d tried, it had been about the dishwasher, and he’d accused it of being a Soviet plot.

Twenty minutes later she returned. Holding a receipt. And a bottle of champagne.

“Verified,” she said. “We’ve won. We are, as they say, loaded.”

William stared at the bottle. Then at the receipt. Then at Wendy, who was now dancing a small jig with the dog.

“This,” he said solemnly, “is exactly what the lizard people want us to believe.”

Wendy popped the cork. It hit William on the forehead. He sat down abruptly.

“Fine,” he said, blinking. “Let’s assume—for the sake of argument—that it’s real. What now? Shall we invest it all in off-shore goat sanctuaries? Or are you going to buy yourself a small nation?”

“I thought we’d start with a new toaster,” she said, pouring herself a glass.

William blinked.

“…That’s actually quite sensible,” he muttered.

“I know,” said Wendy. “Scary, isn’t it?”