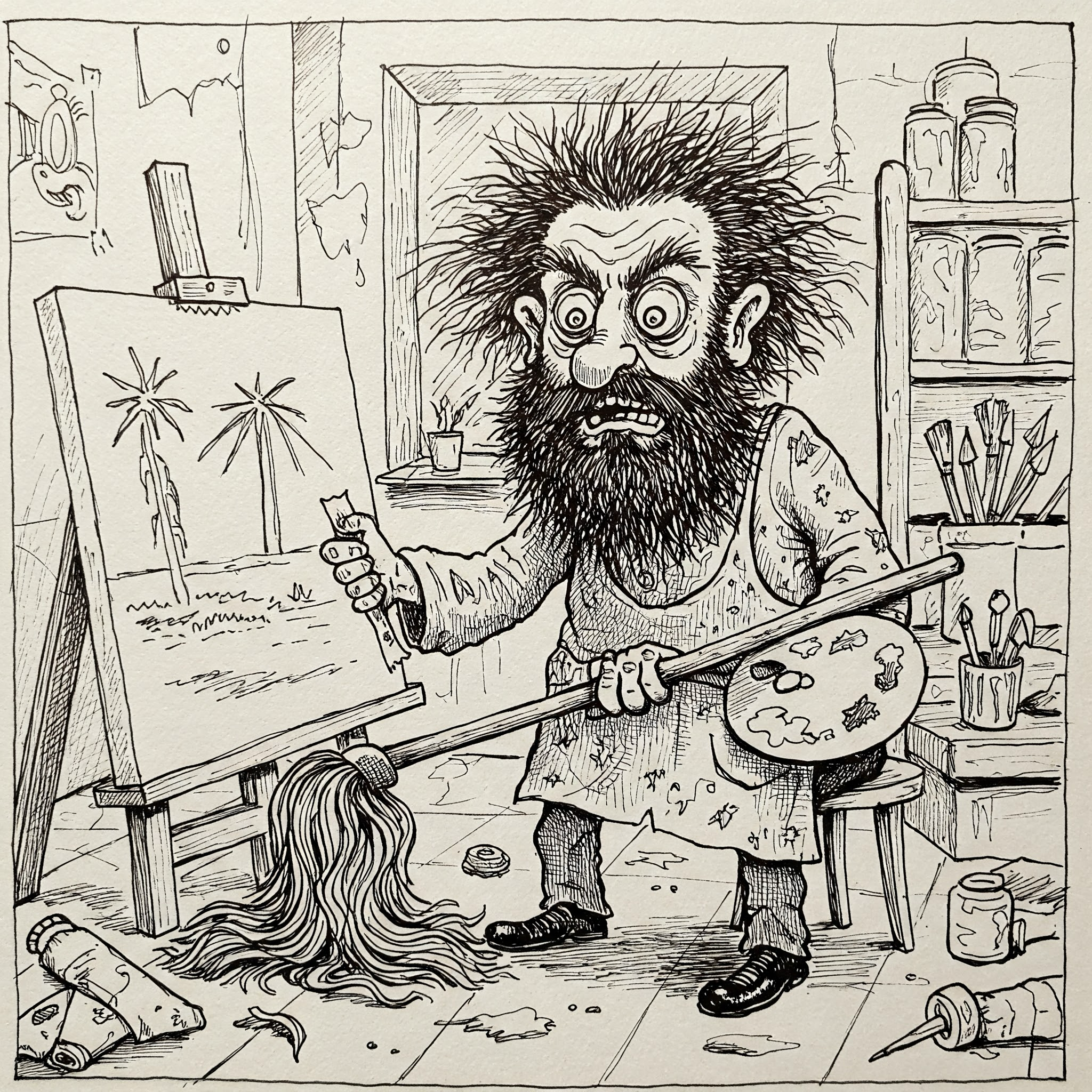

Rupert Fudge considered himself an artist, though few others did. His paintings—murky blobs of angst and pretension—had failed to impress galleries, critics, or even his mother, who once mistook his Ode to Despair for a dirty tea towel.

Desperate for recognition (and rent money), Rupert decided to abandon his usual “interpretive existentialism” and go for something bold. Something shocking. Something that would force the art world to take notice.

So, one afternoon, fuelled by cheap wine and sheer desperation, he splashed an entire tin of emulsion paint over an old canvas, stuck a mop to the middle, and titled it Capitalism Is a Mop.

By sheer fluke, the piece caught the eye of Esme Clench, an influential art critic notorious for declaring dead pigeons as “post-modern reflections on decay.” She took one look at Rupert’s creation and nearly fainted. “This,” she gasped, “is a masterpiece.”

Within a week, Rupert was a sensation. His work was hailed as a brutal critique of consumerism, oppression, and possibly plumbing. The Tate Modern commissioned Capitalism Is a Mop II for an obscene sum. Rupert, who had no idea how he’d created the first one, simply threw paint at a new canvas and stapled a toilet brush to it. It sold for £200,000.

Everything was going perfectly until the BBC Arts correspondent, while investigating Rupert’s “radical new technique,” discovered something troubling. Capitalism Is a Mop was not, in fact, an original work. It was a repainted sign from the local launderette. When confronted, Rupert tried to bluff his way out.

“Of course it’s a launderette sign! That’s the point!” he insisted. “It’s a damning statement on—on the cyclical futility of existence!”

Alas, the public did not buy it. Outrage erupted. XR exploded with furious denunciations. Galleries that had fawned over his work now tripped over themselves to denounce him. Someone started a petition titled Mopgate: Return the Money!

Rupert tried to defend himself. “Is it my fault that nobody noticed it was a sign before? Doesn’t that say more about the art world than it does about me?”

The only person who agreed was his landlady, who promptly doubled his rent, saying, “If you’re going to profit off rubbish, you might as well pay for the privilege.”

And so, Rupert’s career ended as quickly as it began. His work was removed from galleries, critics pretended they had always found him tiresome, and Capitalism Is a Mop was last seen propping open a fire exit at the Tate.

Still, all was not lost. A week later, Rupert received a call from a trendy advertising agency. “We love your work,” they said. “How do you feel about designing a new campaign for a cleaning supplies brand?”

Rupert took the job.

He might not have been a great artist, but at least he finally had enough money to pay his rent.