There were few things in life that Rupert Montague hated more than being sober at a poetry reading, but one of them was not writing. Writing was his oxygen, his mistress, his drug—he needed to write the way lesser men needed food, sex, or basic social decorum.

His neighbours called him “eccentric.” His ex-wife called him “unbearable.” His agent called him “on indefinite sabbatical.”

But Rupert? Rupert called himself a vessel of words. The problem was that the vessel had no outlet.

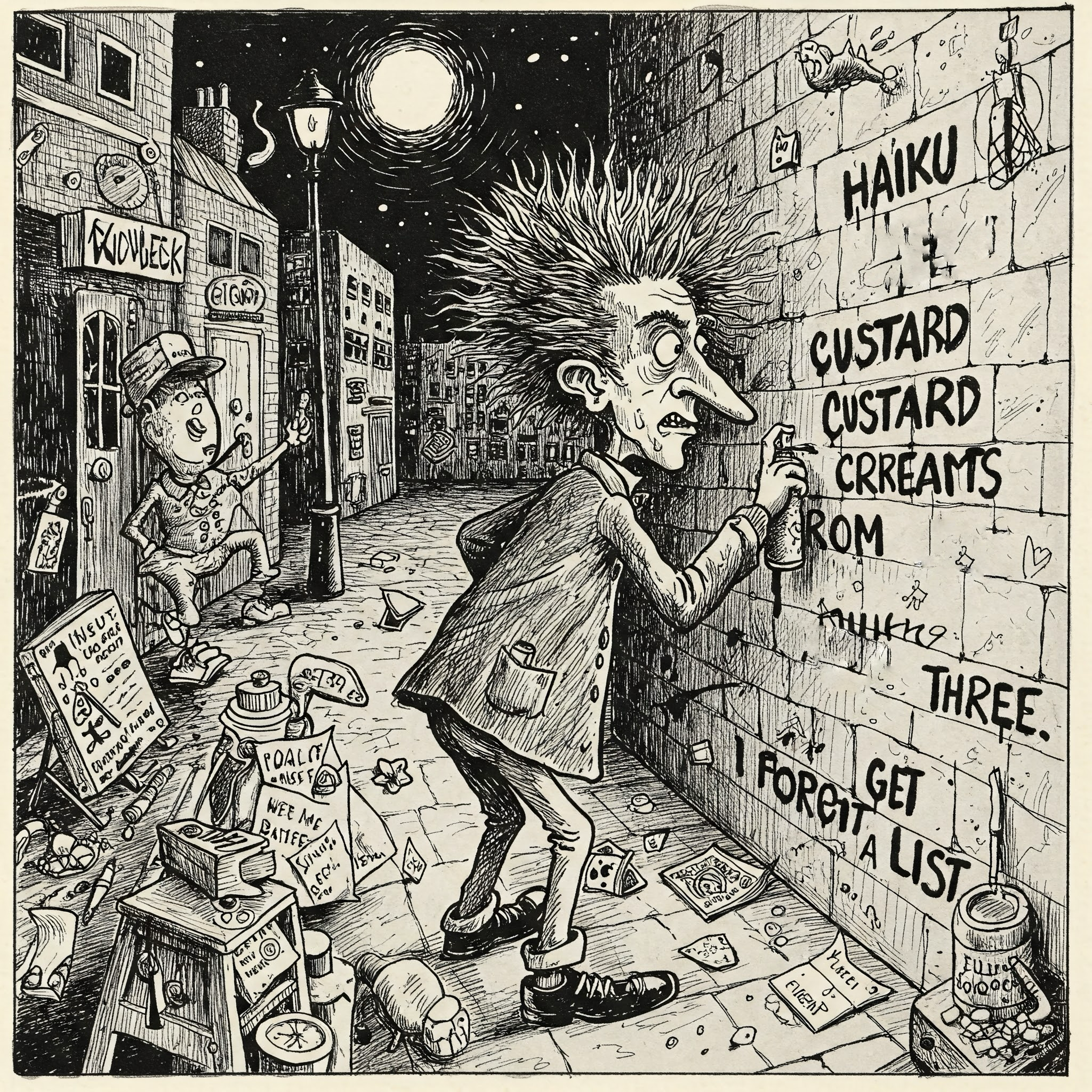

Which is why, at precisely 2:43 on a rainy Tuesday morning, Rupert found himself in a Sainsbury’s car park, spray can in hand, daubing seventeen syllables of questionable profundity onto a corrugated metal wall.

Shopping trolleys dream

Of wild geese and fallen leaves.

Pound coin holds them fast.

He stood back, admiring his work. It was, in his mind, his finest poem since the regrettable “Ode to a Biscuit” phase of 2019.

⸻

By Friday, there were haikus all over town. On bus stops, bins, the side of the mayor’s Prius. No surface was safe. Passersby were perplexed. Commuters squinted. A local councillor burst into tears after reading one painted on the war memorial.

The town’s paper ran the headline: “WHO IS THE HAIKU HOOLIGAN?”

Rupert, meanwhile, had never been happier. He wrote like a man possessed. He tagged road signs. He wrote a haiku on a cow.

Moo echoes through mist.

Grass chewed in contemplative

silence of the damned.

The cow, entirely uninterested in poetry, kicked him.

⸻

The situation reached its peak when Chief Inspector Derek Blenkinsop, a man of such relentless joylessness that even sudoku feared him, was assigned to the case.

“This is not art,” Blenkinsop said, as he examined a haiku written on the statue of Queen Victoria.

Monarch unmoving,

pigeons crown thee daily with

democratic gifts.

“It’s anarchy.”

His sergeant, who had done a degree in Comparative Literature and spent most days trying not to show it, squinted.

“Well sir, technically, the syllable structure is quite elegant.”

Blenkinsop turned slowly, his moustache twitching with suspicion. “Are you sympathising with the vandal?”

“No sir. Just noting his grasp of form.”

“Form? FORM? I want CCTV, DNA, and if possible, a sample of this man’s bloody muse!”

⸻

The downfall came, inevitably, due to a Tesco Express.

Rupert, believing himself invisible, was caught on camera tagging the automatic doors with:

Doors glide like silence.

Custard creams watch from aisle three.

I forget my list.

The footage went viral. Rupert was arrested mid-stanza behind a Lidl, caught red-handed and mid-line:

Tarmac holds my steps—

like the—

“Like the what, sir?” said Blenkinsop, pinning him to the ground.

Rupert blinked up at him with the tragic dignity of a misunderstood genius. “Like the cold, unyielding grip of societal repression.”

Blenkinsop tightened the cuffs. “Right. That’s resisting arrest and being a pillock.”

⸻

At the trial, Rupert represented himself.

“I did it,” he declared, “not for fame, nor glory—but for syllables! For balance! For the raw, unvarnished beauty of the moment!”

The magistrate, a woman whose favourite poem was “Roses are red,” sentenced him to six months’ community service and mandatory rhyming therapy.

⸻

He now teaches haiku to a group of mildly criminal pensioners at the community centre every Thursday.

He has stopped spray painting, but occasionally eyes the walls with longing.

His most recent poem was written in biro on a toilet roll dispenser:

Judge not, gentle loo.

We all flush what shames us most.

And hope no one hears.